As a business professor, I teach mostly undergraduates. It is shocking and saddening how many of them share that they are going into a profession or field of study because it is what their grandmother hopes they will do or one of their parents thinks they will be good at. Or their father was a dentist as was his father before him and so that is what the 20-something standing before me as we chat after class thinks he should do. I’ll often ask, “What do you want to do?” or “What interests you?” Their response is often a dumbfounded look associated with a lengthy pause, and then something along the lines of, “Hmmm…I’m not sure. I never really thought about it.”

How many of us go through life not really deciding for ourselves but just letting life happen? Or worse, how often do we unconsciously let others make decisions for us? Sometimes it is through the pressure applied by those we love where we give in to what they want, and other times we give up our decision rights without even realizing what is happening. We give in to what others want for us rather than choosing what we want for ourselves. We subjugate our needs to the needs of others. Or worse, we fail to realize that we have needs—and that it is okay to have our own needs —and to strive to get those needs met. We live as if our lives belong to others.

About once a year I see an individual student struggle with important life decisions. Quite often it is a female student who comes to my office distressed about the decision to be a parent. She knows she wants a career and is considering delaying having children or not having children at all. In the Utah culture having children shortly after marriage is common and often expected so pressure to have children is immediate and constant after they are married until they have children. Many of my undergraduate students are already married as followers of Utah’s predominant religion of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, often referred to as Mormonism. They feel trapped and in a no-win situation. Caught between what they want and what others want for them. If they do what is expected, they disappoint themselves. If they do not do what is expected, they disappoint others. They are caught in a double-bind on a decision that invariably has life altering implications. Many of them were children of stay-at-home mothers and thus who have little frame of reference for other life choices. Thus, the pressure can be compounded not just by the culture we live in, but the family in which we are raised.

Who is choosing your life? Who is living your life? Is it you? Or does someone else have the reins? Are you making the decisions that shape your life and thus your happiness? Or is someone else in your life being allowed to live your life by making choices for you? Those may sound like odd questions because “Of course I’m making my own decisions!” However, our lives are made up of the choices that we make. Failing to make a decision is sometimes the path that we take! Our lives are shaped by the decisions we make that result in increasing our happiness. Our lives are influenced by the decisions that we regret because they led to unhappiness, stress, or disappointment. You are the primary recipient of the consequences of your decisions. Others may experience the ripple effect of your choices, but you are the main beneficiary of the joy or unpleasantness that follows your decisions and associated actions. Your life belongs to you. Not to your significant other. Not to your children or your parents. Not to your siblings or well-meaning in-laws. Not to your friends. Not to your church. Not to your employer. Your life belongs to YOU.

When others try to influence our decisions or make decisions for us, it is rarely out of malice. Especially when it is those closest to us, they are often looking out for us and trying to help us live our best lives. However, allowing others to make our decisions is dangerous both for us and for the other party. First, we bear the brunt of our decisions and must live with the associated consequences, more so than those trying to decide for us. Second, if we let others decide for us, then they get the credit or the blame for the fallout. In other words, if a decision results in a good outcome, we may credit the other person or party for that instead of patting ourselves on the back. In doing so, we miss an opportunity to build trust with ourselves and confidence in our abilities to make wise, strategic decisions. Similarly, if the decision yields a negative outcome, we may blame the other party rather than owning the decision and its outcome ourselves. This may lead us to keep making poor decisions because we have not internalized that a decision or an action leads to an unpleasant result and so we keep making decisions that do not increase our happiness or productivity. Thus, letting others decide for us means we may not learn from either our good or bad decisions.

How we think or don’t think about decisions is key. In his best selling book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Nobel Prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman proposes that our thinking and thus our decision making falls into two categories – System 1 versus System 2. System 1 is characterized as automatic, frequent, unconscious and fast. Conversely, System 2 is effortful, infrequent, conscious and slow. For example, we often use System 1 when we drive a car and must quickly decide if we should brake for the stop sign at the intersection that lies ahead or that we need to speed up in order to merge onto a busy freeway. However, a less experienced driver may engage in more System 2 thinking when they are making new and less familiar decisions as they navigate the road and other drivers.

We might hope that life’s big and consequential decisions are strictly driven by System 2 thinking but as the anecdotes above suggest, they often are not. Instead, we can be tempted to yield to what others want, particularly if the decision is of a type with which we have less knowledge or experience. This could be with the goal of making the other person happy. Or it could be because we think they know better or more than we do. We may give up our right to make a decision by engaging in System 1 thinking and letting others decide for us.

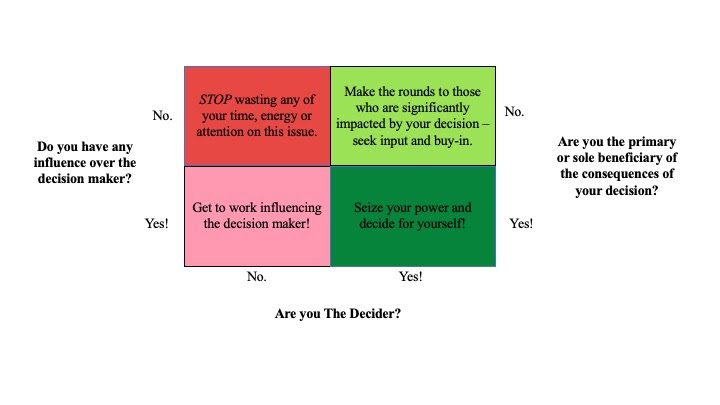

One framework useful in shaping how you think about the decisions that potentially involve you and determine what your role may be in the decision making process is shown in the figure to the right. On the bottom, the framework addresses the factor of whether you are The Decider, as former president George W. Bush used to say (with the requisite Texas accent). In other words, do you get to make this decision? Do you have the right to make the decision? Do you get to own the decision?